A good photo hasn’t fulfilled its destiny until it has been well printed. This is why I’ve always made sure that my clients get prints, at least of the best and most important photos. It’s why I want prints for myself.

In the past, I ordered prints for clients through my lab. I still do. But, for the last couple of years, since the release of affordable high-end desktop photo printers from Canon — like the PIXMA Pro-1, or the Pro-100 and Pro 9000 MkII — it has become possible for me to do more and more of this work myself, and to do that work really well. I want to say a little here about the ways this has changed my approach to taking photographs and why I find this change exciting. Printing isn’t everybody’s cup of tea, so I’m keeping this as personal as possible.

NOTE: I mention Canon only because that’s what I know. I gather from printers I know and respect that Epson makes terrific high-end printers, fully competitive with those from Canon. I just have never owned a really good Epson printer. This Epson vs Canon issue, however, is completely beside the point of what follows.

Excellence and affordability

Of course, the prints I make myself on my best printers are also excellent in the basic technical sense. In terms of qualities like color, tonality, detail and longevity, the best prints I make now are at least as good as those I get from the lab. If they weren’t, I wouldn’t bother. And while the cost of the raw materials I use making to make a print on my own is higher than the cost of a print from the lab, the costs are no longer prohibitive. Do-it-yourself high-quality printing is expensive, but affordable.

But excellence and affordability are basically negatives. They just mean there’s no reason for me not to do it. What are the positive things about printing for myself that make it worth the trouble?

Immediacy and control

With respect to printing, “immediacy” and “control” mean something very like what they mean with respect to taking the photo in the first place on a digital camera. It’s not that I get the final outstanding result immediately. It’s that I can identify failures or mistakes or weaknesses immediately and immediately make adjustments and improvements.

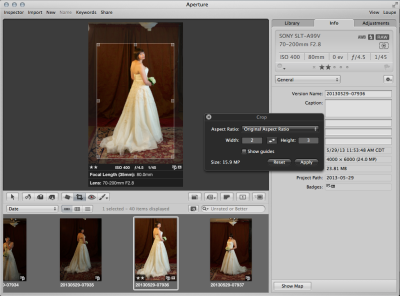

On occasion, I’ve gotten prints back from the lab that had problems: color might not be right, or I see that the crop isn’t perfect, or on second thought I don’t like the tonality of the image. I could make adjustments and send the file back to the lab, then wait 3 days to find out if the changes did the trick. But generally I don’t. Generally, I work hard to get things as close to perfect before sending images to the lab. And then I live with what the lab sends me.

It’s really very like the difference between eating at a restaurant and cooking for yourself. If I go to a great restaurant, I can get a great meal. But generally speaking, I eat (and pay for) whatever they bring to the table, whether it’s exactly what I was expecting or not. Cooking for myself, on the other hand, takes time and effort. But I’m cooking a dish I’m good at, I can count on my wife or daughter saying out loud that it’s better than we’d get at a restaurant.

So it is with making my own prints. Now that I have reached at least basic competence with most of the various challenges that printing presents — not just color management, but image preparation, paper choice and handling and more — I don’t have to live with what somebody else gives me. If I’m not completely happy with the result, I can tweak it and print it again.

And that brings me at last to the things that really explain why I do this. I do it because I personally find it very satisfying — and because I am convinced that making my own prints has been making me a better photographer.

Satisfaction — and purpose

The analogy between cooking and printing isn’t perfect. I like to cook and so long as I keep things simple, I’m a decent cook. But mainly, I like to eat. If I were a gazillionaire, I’d hire a chef to cook for me or I’d eat out every night at excellent restaurants. For me, eating the meal is not just the final goal, it’s the entire goal. It’s nice to get compliments when I’ve cooked a good meal, but I don’t need them. If I enjoy the meal myself, that’s enough. And while I do remember a handful of particularly successful outings in the kitchen, by and large, the pleasure of a meal is emphemeral.

Making a printed image is very different.

For one thing, the printed image endures. As I write this, I can look up and turn my glance in any direction and see prints of my photos on every wall. These prints will outlive me.

And every print gives me a satisfaction that is very hard to describe. It’s the satisfaction of having taken an image from concept to capture to development to embodiment in a print — from idea to something tangible, unique and valuable. There is pleasure in setting up the shot, getting the model (whether the model has two feet or four) posed and lighted correctly, waiting for the right expression and so on. There’s pleasure in clicking the shutter and knowing — without having to chimp — that the shot was nailed and will be good. There’s pleasure in reviewing the photo on the computer and developing it, converting the raw file and making the adjustments that are beyond the camera’s ability. And there’s great pleasure in watching for a minute or two as the print comes out of the printer, one row of pixels at a time.

The “virtuous cycle”

And in the end, all these satisfactions turn back on themselves in a kind of feedback loop or “virtuous cycle”. I mean by that mainly that seeing prints of my photos has made me a better photographer. Printing photos is a real test of quality — the ultimate test of quality, I think. That’s why I think that, whether you print your photos or order prints from a good lab, every serious photographer should make prints. At the start of this post I wrote:

A good photo hasn’t fulfilled its destiny until it has been well printed.

The modifiers (“good photo”, “well printed”) are important here. The initial question is always: Is the photo worth the paper I’m thinking of printing it on? It’s depressing and, well, discouraging, at first, to discover that quite often the answer is simply no. Here’s a decent pic I took a couple of weeks ago of some flowers I gave my wife. But I’m not going to print it. The flowers were more important than the photo, and the flowers have already wilted. Here’s a cute photo I took with my phone of my dog Arthur at the vet. I sent it to my oldest daughter, who loves Arthur almost as much as I do, to let her know he was under the weather. It’s not a bad snap, but I’m not going to print it.

So I print it. My guess is, that’s perhaps 1% of the photos I take — certainly less than 5%. Many of that 1% get printed and then thrown away; some get filed in a drawer or folder; others get placed in a photo album. And those final, lucky few? The 1% of the 1%? I pick them up with my white-gloved hands from the printer tray and think to myself, Eureka! This one is worth spending $20 (or $200) to frame. This one is worth giving a place permanently on the walls of my home or office.

That’s a happy day.

But whether the photo ends up in the trash, in a folder, or in a frame, the process of printing and review generates the feedback loop aspect of printing my own photos. I didn’t always do this in the past, but now, I shoot with prints in mind. Not sometimes, but always. And that makes me work more carefully. You can’t work in careless point-and-shoot mode some of the time and turn on the quality at others. At least, I can’t.

And having shot for the print, I want to see the print as fast as possible. Making the prints myself speeds up that feedback loop. I find out more quickly what I’ve done wrong and what I’ve done right. And in turn, my growth as a photographer feeds my growth as a printer.

The upshot of all this may strike you as odd: I’m satisfied with fewer and fewer of the photos I take. But that’s been prompting me to take fewer and fewer photos and try to increase the number of “keepers”. And when I do take a good one, well, then it all seems worth while.

Q.E.D.